- Home

- Andrzej Stasiuk

Dukla Page 10

Dukla Read online

Page 10

For a long time I was unable to free myself of that image: Two people I didn’t know climb into a boat. They’re poor, but dressed up. The man is in a dark ill-fitting jacket and a white shirt fastened at the neck. He smells of mothballs. The woman’s wearing a simple dress the color of photographic sepia. She has a headscarf on. She’s carrying a bundle in her arms. The boat pitches. The woman is frightened. The man reassures her and tells her to sit down on the narrow bench. He himself takes up a long oar with a metal fitting at the end and pushes off from the shore. They’re both barefoot. Their shoes are placed on the bench next to the woman. The boat leaks. It’s possible the man takes off his jacket. It’s hot. The sun is shining directly overhead. Their bank soon becomes as distant as the one they’re heading for. In the middle of the water they can scarcely be seen. The woman is increasingly afraid, because she’s never been so far away from the whole world in all her life. In fact, her fear is twofold. And the man knows she’s frightened, but he’s also aware that on this occasion he can’t tell her off, so he merely repeats that it’s not far now. He too is anxious in a way he’s never felt before. He bends low and immerses the oar all the way up to the crosspiece at the end of the handle, but he’s still out of his depth and has to row with a narrow blade meant only for shallow water. For eternally long moments they’re lonelier than they’ve ever been before, and probably than they’ll ever be again. He stands behind her and can see only her back and her arms, curled in their embrace. The woman lacks the courage to shift or turn around. Her lips move soundlessly. When they find themselves in the middle of the current, the space around them becomes still and they’re sure they will never reach the other side, though there are already dark patches on the man’s white shirt. When the prow of the boat finally pushes in among the bulrushes they can’t believe it. On their return journey they have one less anxiety. The child is baptized now and in much less danger. The sun has swung to the west and to their left they’re accompanied by their shadows.

As we crossed back over the island I asked my grandfather why they’d rowed across the river since the church was on the same side. True, it was six miles away, but it was on solid ground and a regular road led to it. “I don’t know,” he said. “Maybe they didn’t have a horse and it was quicker by water. In those days a lot of children died and people were afraid. Everyone was in a hurry.”

We made it over the Break in a few minutes. It grew tiny. We’d barely pushed off and already we were at the other side. The cows of the entire village had gathered along the bank. Some of them were in up to their knees, drinking. Along with ooze, fish, and willows, that was a fourth smell to the half lifeless water: cows. The smell of milk, warm animal hair, and greenish cowshit. They stood there in the shallows with their tails raised releasing watery streams that splashed into the river. They were being minded by an old guy who was known as “the Shepherd.” He’d take turns eating in each of the homes in the village. I don’t know if he got any money for what he did. It didn’t look like he needed any. Plus, his bizarre, ragged outfit may not even have had pockets. He carried a stick and wore a hooded cloak that he never took off even in the hottest weather. At dawn he’d collect the cattle from the farmyards, then bring them back in the evening. He’d lead the herd through the village and each cow would unfailingly find its own farm. You only had to leave the gate open. The same in the morning, they’d join the procession without being told, lowing to one another. They were like a slow living pendulum that moved along the fences twice a day, there and back again, measuring out time in the village. A clock made of flesh, a mechanism of blood and bone, indolent, straggling, but inexorable. No one paid any heed to the ticking and chiming of the longcase clock in the dark living room, though my grandfather wound it up daily with a special key. Perhaps he just regarded it as another head of livestock that needed regular care, while the hours it rang were quite unconnected with actual time and were simply a folly, a whim, an extravagance, like the Pionier radio that played Stenia Kozłowska songs from the capital.

When we got out of the boat, my grandfather found his own cows among the dozens that were there. He went up, checked them over, and said something I didn’t catch. He didn’t so much as glance at the Shepherd.

And now, on this late April afternoon in Żmigród, I was a grown-up and I could do what I pleased. I went to the square near the post office. It was deserted. The merchants had gone. They’d taken away the scaffolding where they hung their colorful electrostatic wares. When the wind blew, sparks would crackle in among the blouses and shirts. The shiny multicolored garments would fill with air; women would touch the phantoms, taking the fabric between their fingers, rubbing it with knowing pleasure and admiration, imagining their own bodies in place of the air. Yellow, orange, pink; gold buttons, frills, plastic brooches, chains, flounces, red lacquer, the fragile tinplate of buckles, stilettos with pointed toes and heels narrow as an umbrella ferrule, frothy jabots, shadowy low-cut necklines, the flora and fauna of appliqués, glassy markings of sequins, the polymeric sheen of lizard-pattern Lycra and the entomological transparency of puffy nylons with their pyrogenic lacework, stars, distant lands, wistful planetaria, the luciferic fictions of knitwear, moon-shaped clip-on earrings, knickknacks with holes, snakeskin, hairclips aspiring to be suns.

All this put me in mind of my grandfather’s litany. As he kneeled amid the paper flowers, his body would gradually free itself of the torment of constant movement, the miracle-working pictures would unbind it and the mind turn flesh into light, while the “golden home” enclosed him in its walls and bore him to a space beyond the village, beyond the world, where reality became transformed, as did the torments of everyday life, even his membership of the volunteer fire brigade and his position as village chairman. It’s entirely possible he found himself there with the whole village, all his worldly belongings, the stretch of pine grove he owned, his “crazy sons” as he called my uncles, and everything else in the world, including the firehouse and the squire’s old mansion; The Paris Commune may also have been similarly favored, because, after all, matter is indivisible and when you agree to A you can’t thumb your nose at B.

So then, as I stood there in Żmigród imagining the clothes market from that morning, I could see my grandfather relishing the successive invocations, the same way the women on the square had relished the marvelous outfits on sale that were magically imbued with their dreams of respite, of a sudden change of fate, a miracle of light, purity, of a shining that would heal, elevate, soothe their sad bodies that were locked in a desperate cycle of actions, of the beginning of one and the end of another, an end that was nowhere in sight.

At number two on the market square in Dukla there was a general store with a display window the size of a ticket window at a small train station. Generic herbal shampoo, green combs, Ludwik dish detergent, suntan lotion, sashes of linen rags, pink sponges, plain wire hairpins, a gold plastic openwork wastebasket, a pale blue china rabbit with a sugar bowl on its back, and three tattered rolls of toilet paper stacked in a pyramid. There’s no accompanying sign, the things are what they are. They’re fading in the sunlight since the window faces south. They’re getting old, because the business has few customers. People prefer to visit actual stores rather than a place that looks like their own home.

This was later, in the summer. I was standing staring at this bizarre display, while my shadow lay half on the ground and half against the wall. The banal objects in the window suddenly took on the kind of significance the surrealists always dreamed of. The lack of a shop sign and the absence of any inscription left them utterly orphaned by everydayness. They were tragic caricatures. I lacked the courage to enter and look the heroic proprietor in the face. It was as if in this place the world had stopped flowing, as if it had frozen so as to show the meaning of immobilized change, the cruelty of a present strung between the desire for tomorrow and the possibility of yesterday. It was like makeup on a sixty-year-old woman

, or a senior citizens’ soccer match, or an old automobile proudly driving along under its own steam, unaware it’s being taken to the junkyard.

And as I stood there with the sun at my back, I remembered our dog Blackie, who was already blind and deaf, and barely knew who we were; one day he disappeared, vanished somewhere, and though we looked for him for days we never found him, it was as if he’d wanted to leave us the hope that he’d simply gone away, the same way he’d just appeared one day ten or fifteen years earlier. And I thought to myself that if animals ever invented a religion, they would worship pure space, just as our own madness constantly revolves around time.

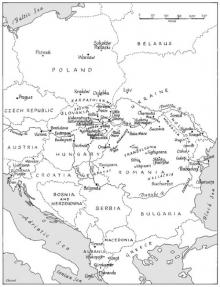

So it was summer already, and Dukla again, though this time I’d come in from the south. We’d spent two days visiting the Spiš region of Slovakia. The blueish heat eased a little in the valleys, but whenever the road climbed higher onto the vast languid mountain ridges with no shade, it resumed its glassy structure and far into the distance you could see successive hills swathed in hazy golden cornfields with the red bugs of distant combine harvesters as if in a collectivized land of plenty, because the whole was completely undivided by any field boundaries or country roads, nothing but gold down below, azure up above, and blue road signs with the names of the towns and villages.

In the late afternoon we parked on the market square in Podolínec along with four other cars, all old. The houses had been where they were for two or three hundred years. The few people around all resembled each other. Two Gypsies followed us with their eyes, then returned to their cigarettes and their silence. There were two or three others with them. One was pushing a moped loaded with mown grass. We passed him on the long street that runs by the square. There was nothing but barns along it. Large, ramshackle, their gables pointing toward the road. There was also a flock of white turkeys. Aside from the moped there wasn’t a living soul, not a creak, not the trace of a sound, only buildings. We could feel a kind of presence, but it was somehow diluted. In places there was some movement far down an alley, something was happening, but it was too little for a sizeable town. A kind of timelessness hung over everything. M. told me afterward she’d found it the kind of place you’d want to stay in forever, without giving any particular reason, while I thought to myself that there are places where everything we’ve been up to the present moment is gently and profoundly brought into question, and we feel a bit like, say, a bird that suddenly realizes it has no air under its wings, but instead of disaster we find ourselves facing an endlessly long rest, a boundless soft falling. That was how it was in Podolínec. It looked like a town whose supply of things to happen had run out. Even C. kept talking only about the past, though the whole way there he’d been wrapped up in practical romantic plans.

But in the end we drove on, because we wanted to get something to drink before nightfall. Though it may also have been a self-protective reflex, a fear that our life would start mocking its own more or less established forms.

We were saved by Spišská Belá. We found something there that was half alleyway, half tiny market square where women perched on the steps in front of their houses and watched their menfolk, who were sitting on benches a few yards way in the dark blue late afternoon shade, drinking Smädný Mních or ordinary Šariš out of green bottles. Close by, in the corner building there was a little store. Inside, the place had a hazy yellow glow, rather like in a dream, mysterious, as if from some other time, from before the war, but all the things in there were real. They had tar-black Fernet, and Velkopopovický, though only the No. 10, and Chesterfields in the short Slovak version.

We kept driving and driving, but the day wouldn’t end. In the small towns, between the walls, it was already late, but the moment we found ourselves out in open country the light gained in strength. Architecture and geography were playing mental blindman’s buff with us.

Along the road to Kežmarok, Gypsies had taken up residence in the middle of nowhere. All around, as far as the eye could see there were miles and miles of meadows, while somewhere in their imagined middle was a lone concrete block. Nothing more, just that: gray, angular, crumbling. Dark-skinned children gave us a friendly wave. Guys were standing around in groups, laundry was drying, and you could see there was an atmosphere of calm unconstraint peculiar to people accustomed to waiting. They’d commandeered this chunky Corbusieresque piece of work and thereby lessened its ugliness, because they’d caused it to lose all signs of permanence. Neglected, dirty, hung about with rags, surrounded by shacks and junk, it was slowly turning into something mineral and subject to erosion. In this way a creation of high civilization had been occupied by a distant archaic tribe solely so it could be returned to the indifferent world of nature.

Then there was Kežmarok. It had the obligatory stork’s nest on a tall chimney, alleyways, and little apartment houses with façades that C. knew a lot about, while I saw in them only various stages of decay: ongoing, arrested, or past continuous, temporarily turned back by the hands of painters and stucco-workers.

We had garlic soup at an outdoor restaurant where there were soldiers in green fatigues. Alas, they weren’t drunk and they were not singing. They looked more like underage drinkers enjoying an illicit beer. They seemed like a very tranquil sort of army, I thought. After all, they’d never won or lost any war. After the soup we ordered sausage, because C. really took a shine to the waitress and he kept wanting to order something else, he kept forgetting something or other, and after his third beer we had to remind him he was driving. He agreed with us completely, and as a compromise, for the fourth round he only ordered a small one. We waited for dusk to fall over Kežmarok, so everything around us would disappear and there’d be darkness, which is the same everywhere, and allows you to breathe freely.

The next day we went to Levoča, because someone had told us the food was good at U Troch Apoštolov, but the place was too stuffy-smart so we went to Janus’s on Kláštorská. The people at the tables looked like hyperreal portraits. It was brighter than in Poland at the same hour. The woman at the next table lit a cigarette but I didn’t see the flame, just the smoke, all at once. We’d crossed the Carpathians, fled their northern shadow, and all of a sudden light was omnipresent. It emerged from the walls, the sky, the pavement, as if the sun had lost its monopoly and now the objects newly liberated from it were producing their own light, or at least trying to store it up. The dumplings, gravy, potatoes, sausage, and cabbage still belonged to the north, but everything else was more like fire than earth. The sulfurous yellow walls of the buildings, the red and orange and pink of flowers in the window boxes of crumbling apartment houses on Vysoká, sweat and suntan, the tedium of the bluish void with the livid Poprad highway like a dead snake lying belly-up, and the bar with no sign where dark-skinned, tattooed men in T-shirts sat drinking Šariš beer and flipping the levers of a pinball machine, and the only woman was a pale, skinny barmaid. A bit farther on, sitting on some steps was another girl, swarthy, dark-eyed, with dyed blonde hair. She was holding a baby, while next to her lay a pack of LMs, and when we came back the same way an hour later nothing had changed except the pack of cigarettes was almost empty, and that was exactly what afternoons looked like on Vysoká Street. Afternoons on the south side of town, on the sun-scorched, burned-out slopes that dropped toward Levočsky Creek, with the yellow houses that looked frail and flammable, and even though they were built of stone, and even though they were handsome, you couldn’t help feeling they were temporary, that they’d been temporary for three hundred years, because they lacked the definitive weightiness of buildings in the north, where they constitute one’s sole, indispensable shelter.

We turned into Žiacka; here it was siesta time. The Gypsies gave us unfriendly stares, though we weren’t so different from them. We were poor too, and we too were killing time. They were sitting on walls, steps, benches, listening to their music on tape players. The glare of the sun settled on their bodies and disappeared. They were like ripe fruit. Labo

rers were demolishing a house on the corner, but the Gypsies didn’t even look at them. Right nearby someone’s world was coming to an end and it didn’t bother them in the slightest. The music drowned out the din of collapsing walls. The afternoon’s vertical white dazzle blurred the shadows, and Žiacka looked like the alleyway of eternity, or an icon.

We went to St. James’s. The famous altarpiece by Master Pavol of Levoča was decidedly too small. The doll-like Gothic looked as though it had only just gone on display. People were wandering in every direction, craning their necks. For two korunas you could listen to a history talk from a metal cabinet. I was drawn to the confessionals, though: both confessor and penitent could enclose themselves in a huge wooden chest. Not like in Poland, where the sinner has to kneel before the eyes of the entire church, his only thought how to rise as quickly as possible and melt back into the throng of decent folk.

From St. James’s we walked down Sirotínska toward the city walls, then to the Franciscan monastery. The shadows of the stone building were cool and deserted. We saw an old woman squatting against the wall of the church and peeing. We slowed down to give her time. She unhurriedly pulled up her stout pink underwear and let down her skirt. She was wearing a headscarf. She didn’t look at us but simply disappeared around the corner. A minute later we saw her inside the half-empty church, joining the old ladies sitting in the pews. They were reciting a litany to the Holy Spirit. Our new acquaintance had slipped out between the first invocation and the second, and now she resumed her place. She reminded me of the women who used to gather in my grandfather’s house on Sundays, then trek over to the church four miles away. The sandy road led through pinewoods. It was hot, dust would be hanging in the air. The horses would be plodding quietly and heavily in their harnesses. Their sweating black and bay rumps glistened in the sun. The women would occasionally take a seat in one of the wagons, but mostly they’d walk. They’d carry their plain black sandals with low heels and their patent leather handbags where they had prayer books with large clear print. Their step was like the step of the horses: lengthy, tense, strong. They sank up to their ankles in the sand. From time to time one of them would lean her hand on the side of a wagon to take a rest, still walking, the way a swimmer rests at the side of a boat. They didn’t perspire. They walked quickly, leaning forward, as though the road led into the wind, and they had strength enough to join in groups and talk. They joked, bantered, and the gold and silver of their teeth flashed with a childlike playfulness. Dust settled on their brown feet. After the hard uneven ground of farmyards and prickly stubble fields, the soft warm path was a relief. They only put their shoes on in front of the church. The more fastidious ones took out a handkerchief and hastily wiped the dust from their feet and calves. Some went in the bushes and peed almost standing, hiking up their Sunday dresses. The horses cooled off in the shade while the men slung nosebags around their necks. The scents of animals and humans mingled over the sun-heated square. Powerful streams of horse urine frothed like beer and instantly soaked into the ground. The smell of sweat-soaked harness straps, horse farts, cigarettes, and soap melted into one, as if Sunday were both a human and an animal holiday. The weather descended upon the church square like an indifferent grace. The girl from next door was wearing a grown-up dress in place of her skimpy red outfit. She looked like the other women and was of no interest.

Dukla

Dukla On the Road to Babadag

On the Road to Babadag Nine

Nine