- Home

- Andrzej Stasiuk

On the Road to Babadag Page 3

On the Road to Babadag Read online

Page 3

"It would have been better for me had I never left this village. I'll never forget the day my parents put me on the cart that took me to the lyceum in town. That was the end of my beautiful dream, the destruction of my world."

Now a tram goes from Răinari to Sibiu. The line loops at the edge of the village. You sit on the steps between the bar and the cobbler. In the bar they sell vodka that tastes of yeast; it's thirty-six percent and cheap. Before the tram arrives, several men down a glass or two. Like that Gypsy we kept meeting for a few days in different places. Once he was waiting for a bus to Păltiniş; another time he was hanging around the station in Sibiu. A black felt hat on his head, a folded scythe and handle in his hands, an old knapsack on his back. It was August, hay-making time, and it's possible he was simply looking for work but couldn't find any or didn't want to, so he killed time, waiting for it all to pass, to end, so he could go back to wherever he came from.

Mornings and evenings we went to the pub on Nicolae Bălcescu Road. You enter down a few steps. Inside, the flies flit and the men sit. We drank coffee and brandy. You could take the same steps to the barber, where there was an antique barber's chair. The place was open late, to ten, eleven, and someone was always in the chair. We also drank beer, Ursus or Silva. From the street came the steady clop of horses. Sometimes, in the dark, you saw sparks from a horseshoe. Every drawn cart had a license plate. The shops worked late into the night. We purchased salami, wine, bread, paprika, watermelon. When the sun set, the shops glowed like warm caves. Our pockets were full of thousand-lei banknotes with Mihai Eminescu on them and hundred-lei coins with Mihai the Brave on them.

"Now, at this moment, I should feel myself a European, a man of the West. But none of that; in my declining years, after a life in which I saw many nations and read many books, I reached the conclusion that the one who is right is the Romanian peasant. Who believes in nothing, who thinks that man is lost, can do nothing, that history will crush him. This ideology of the victim is my idea as well, my philosophy of history."

One evening we went down the mountain to the village. Răinari lay in a valley filled to the brim with heat. I felt its animal proximity. The village gave off a golden blaze, but in the tangle of its side streets there was almost no light at all. The blinds, which during the day kept out the sun, now sealed the feeble light inside the homes. That's how it used to be, I thought. People didn't make unnecessary things; they wasted neither fire nor food. Excess was the duty and privilege of kings. In the square before the Church of Saint Paraskeva, a pack of children had gathered. In the dark, the gleam of chrome from their bicycles. Eighty years ago, little Emil spent the last of his vacation in the shadow of this very shrine. It was August then too, evening, and the boys teased the girls. There just weren't as many bicycles then, and the smell of Hungarian rule still hung in the air, and a few people kept using the name Resinar or Städterdorf. He would be leaving the next day and would never return.

Today, across from my house, four men gather wood. They pull to the forest edge stumps of spruce, stump by stump. When they have three or four, they load them onto a cart. They work like animals—slowly, monotonously, performing the same movements and gestures performed one hundred, two hundred years ago. The downhill road is long and steep. They use stakes to stop the cart. Even braked, the wheels slide on the wet clay. Wrapped in their torn quilted jackets and cloaks, the men seem fashioned from the earth. It's raining. Among the few things that distinguish them from their fathers and forefathers are a chain saw (Swedish) and disposable lighters. Well, and the cart is on tires. All the rest has remained unchanged for two hundred, three hundred years. Their smell, effort, groans, existence follow a form that has endured since unrecorded time. These men are as primeval as the two bay horses in harness. Around them spreads a present as old as the world. At dusk, they finish and leave, their clothes steaming like the backs of the animals.

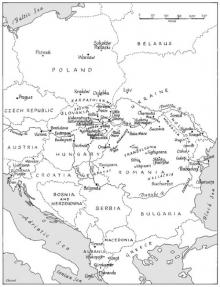

I went out on the veranda to look south again. A truly November dark there, but I was looking back, to last August, and my sight stretched across Bardejov, Sárospatak, Nagykálló, the Bihor Mountains, Sibiu, to reach Răinari on that day at three in the afternoon, when we descended, the black-blue clouds thickening behind us. We went down and down, finally to that mercilessly beshitted field on which stood and lay dozens of red, gray, and spotted cows. Below the field the village began. The first houses were makeshift, scattered, resembling more a camp than a settlement. Over the road and river rose a cliff with young birches; they clung to the vertical rock with the aid of some miracle. Several dozen meters over our heads, a solitary man felled saplings with an ax. Then he tied them together in a knot and let them fall. These sliding bundles knocked stones loose, and the rattling plummet echoed through the valley. At the bottom, women and children waited to pull all this across the river and pile it into wheelbarrows. They were in no hurry. Along the road lay blankets, a campfire, a mangled doll. Their home was a few dozen meters away, yet they had set up another shelter here. Near the fire lay the remains of a meal, plastic bottles, mugs, other things, but we didn't want to pry. One clump of saplings caught halfway down the cliff, and the man slowly lowered himself to free it.

Rain began to fall after we were back inside. I sat at an open window in the attic, listening to the patter on the roof and on the leaves of the grapevine that filled the yard below. The pale mountains in the south darkened like a soaked fabric. A herd of white goats took cover in a thicket. I reflected that he would now be eighty-nine and could be sitting where I sat. This house, after all, belonged to his family. Our host was Petru Cioran. He had Emil's books on his shelf, though I doubt that he ever opened them. Anyway, they were in French and English. He and his wife showed us washed-out photographs: This is Emil when he was eight, and this is Relu, his younger brother. The stocky fifty-year-old man was proud, but every day he ran his store. He got up early, put crates in the van, drove to town for merchandise. At breakfast, we had a shot of slivovitz. It smelled like moonshine, was as strong as pure alcohol, and went well with smoked pork, goat cheese, and paprika.

So Emil could have been sitting here instead of me, could have been watching the rain wet the sacks of cement piled on the platform of the van parked in the street. The pavement shines, the smoke from the chimneys disappears in the gray haze, the water in the gutters swells and gathers trash, and he has returned, as if he never left, and is merely an old man alone with his thoughts. He no longer has the strength to walk in the mountains, nor the wish to chat with the shepherds. He looks, he listens. Philosophy gradually assumes physical shape. It enters his body and destroys it. Paris and traveling were a waste. Without them, things would have gone on a little longer, and boredom would have taken a less sophisticated form. From the kitchen on the ground floor comes the smell of heated fat and the voices of the women. The grapevines gleam and rustle in the rain. Then, from the east, dusk arrives, and the men assemble in the shed by the store. After the long day, they will be tired and dirty. They'll want a bottle of yeast vodka. The woman selling it will give them a thick glass, and they'll finish off the bottle in fifteen minutes. He will hear their talk, which becomes louder and faster, and smell the smell of their bodies through the foliage. The first man will give off tar, the second smoke, the third goats in a stable at the threshold of spring, when the animals begin to reek of urine, musk, and rut. The third will get drunk the quickest, and his friends will hold him up, prop him against a wall, with no interruption in the talk. A pack of Carpati cigarettes will be empty in an hour, and by then they will be drinking yellow beer from green bottles. The gold-gray light from the store's open door mixes with their hot breath, with the stuffy night, making their shapes light, transparent, cleansed of dirt and weariness. Then a couple enters: he swarthy, with a thin mustache, in a plaid jacket, gallant, graceful, boots shining and black trousers pressed, aglow and fluent; she a bit confused, occupied, as if deciding something important. The woman will smile timidly and adjust her peroxide hair. He will entertain her, hop about,

brag, at the same time buy things—chocolate, vodka, beer—and stuff it all in a plastic bag, keeping up the nuptial dance throughout. They drink one beer on the premises, standing and gazing at each other. She from a glass, he from the bottle. Then they leave, arms around each other, into the dark, and her high heels tap the pavement.

So let's assume he heard it all and smelled the perfume through the foliage. The night filled the room in the attic, and he could recall his life without obstacle, because insomnia, just as many years ago in Sibiu, has again taken the place of eternity for him. On Brazilor Avenue and Father Bratu Avenue and Episcopei Avenue and Andrei Saguna Avenue and Ilarie Mitrea Avenue, the animals sleep. In the dim, close barns the cows lie and chew as they sleep. The horses stand with lowered heads at their empty cribs. As it ought to have been and as in fact it is. The heat departs from him forever and over Răinari joins the heat of the livestock. Then it lifts into the black sky above the Carpathians and flows toward the cold stars like a vision of the soul, a vision he couldn't stand, because it kept him awake.

Three months later I was riding, at dusk, through the village Rozpucie at the feet of Słonne Góry, Brine Mountains. The cows were returning from the meadows and taking up the full width of the road. I had to brake, then come to a complete stop. They parted before the car like a lazy reddish wave. In the frosty air, steam puffed from their nostrils. Warm, swollen, indifferent, the animals stared straight ahead, into the distance, because neither objects nor landscape held meaning for them. They simply looked through everything. In Rozpucie too I felt the enormity and continuity of the world around me. At that same hour, in that same dying light, cattle were coming home: from Kiev, say, to Split, from my Rozpucie to Skopje, and the same in Stara Zagora. Scenery and architecture may change, and the breed, and the curve of horn or the color of mane, but the picture remains untouched: between two rows of houses moved a herd of sated cattle. They were accompanied by women in kerchiefs and worn boots, or by children. No isolated island of industrialization, no sleepless metropolis, no spiderweb of roads or railroad lines, could block out this image as old as the world. The human joined with the bestial to wait out the night together.

There will be no miracle, I thought, putting the car in first gear. In the rearview mirror I saw swaying behinds. The tails hung unmoving, because there were no flies now. All this will have to perish in order to survive, if only in rudimentary form. The "worst and smallest" nations live with their animals, and would like to be saved with them. They would like to be respected with their livestock, because they have little else. The dark-blue abyss of a bovine eye is a mirror in which we see ourselves as animate flesh, yet flesh vouchsafed a certain grace.

At the highway I turned left. I wanted to get free of the hairpin turns on the main summit of Brine Mountains before the sun went down. It was empty and cold. Not a soul on the road. In Tyrawa, mist blended with chimney smoke. Here the evening persisted with a will, but after five minutes the sky suddenly cracked and out poured a brilliant red. I left the car at a miserable roadside parking area and walked to the edge of the drop. The highway to Sanok—gray as ashes. In Zału ż, the first lights coming on: weak, barely visible, like pinpricks. The fog in the valley obscured the houses and farms, as if no one were there. On the other hand, the Carpathians were on fire. The western wound stretched across the horizon. The entire south was freshly cut meat, a dazzling slaughterhouse.

I recalled the trip from Cluj to Sighişoara. We went by train. In our compartment sat a Japanese collector of folk costumes and his Romanian interpreter. After Apahida, the grassy plain began. I had never seen earth so naked. Gentle hills in a row in the distance. When the train climbed a little higher, you saw that beyond the horizon was another, and still another. The treeless, uninhabited expanse was a pale, desiccated yellow, the color of something waiting for a tremendous blaze, a single match. Nothing there. On occasion a far building flicked by, a cottage with a pigsty, a hayrick, then again a vastness of air and folded earth. Small flocks of sheep appeared. With them, always, a solitary man no larger than a pin. Under the burned sky, on the baked land, they seemed lost in a blinding afterlife. Going from somewhere to somewhere else. In the brittle grass lived only flies, birds, and lizards. The earth gave off heat and dust.

Now it's a wet, snowless December, and the weather maps say December is in that place too. Like a sheet heavy with water, the sky hangs over Erdély, and the hills are covered with mud and rotting grass instead of dust, and I would like to be there and repeat my summer route, this time getting off at Boju-Catun with ten Romanian words in my head and five Hungarian. I don't remember the station, it was so small and hopeless. Possibly it is nothing more than a metal sign by the rails. But I would like to be there on December 14, with no plan in mind, because the future has not been of concern to me for a long time now and I am drawn increasingly to places that tell of a beginning or else where sadness has the power of fate. In a word, screw where we're headed, I'm interested only in where we came from. So ten words in Romanian, five in Hungarian, the Boju-Catun station, and, let's say, a million lei in small bills, to see the void between heaven and earth through which black buffalo wade. Five hundred kilometers to Vienna, 800 to Munich, 1,800 to Brussels, all of it more or less, approximately, as the crow flies. But the air cracks somewhere en route, parts like tectonic plates separating continents. Yes, a little money, good shoes, something for the rain, Bihor palinka in a plastic bottle, and I'll be fine, because I'm haunted by the vision of those hills; they gleam through all the landscapes I've seen since, because somewhere between Valea Florilor and Ploscoş I believed again that man was fashioned out of clay. Nothing else could have happened in that land, and man grieves only because his making cannot be repeated, ever.

"My country! At all cost I desired to connect with it—but there was nothing to connect with. Neither in its present nor in its past did I find anything genuine ... My mad lover's rage had no object, you could say, because my country crumbled under the force of my gaze. I wished it were as powerful, immoderate, and wild as an evil power, a doom to shake the world, but it was small, modest, and without the qualities that make destiny." So wrote Emil Cioran in 1949, returning in his mind to his adventure in the Iron Guard.

The cows have disappeared into the woods. They moo in the December dimness. Romania Mare, Greater Serbia, Poland from sea to sea ... The incredibly stupid fictions of those countries. A hopeless yearning for what never was, for what can never be, and an adolescent sulk over what is. Last year in Stará L'ubovňa, at the foot of a castle, I overheard the jabber of a Polish tour group. The leader was a forty-year-old moron in Gore-Tex and sunglasses. He knocked at the gate of the museum, which was closed at that hour. Finally he kicked the gate and told those assembled, "It should be ours again, or Hungarian. Then there would be some order!"

Indeed. In this part of the world, everything should be other than it is. The discovery of maps came here too early, or too late.

I drink strong coffee and think constantly about Emil Cioran's broken heart in the 1930s. About his insanity, his Romanian Dostoyevskianism. "Codreanu was in reality a Slav, a kind of Ukrainian hetman," he would say after forty years. Ah, these cruel thoughts. First they devastate the world like a fire or earthquake, and when everything has been consumed and dashed into tiny pieces of shit, when there is nothing around them but desert, wilderness, and the abyss before Creation, they throw away their self-won freedom and submit to a passionate faith in things that are hopeless and causes that are lost. Exactly as if trying to redeem doubt with disinterested love. The loneliness of a liberated mind is as great as the sky over Transylvania. Such a mind wanders like cattle in search of shade or a watering place.

In the end, however, he did return to Răinari. Before the house in which he was born stands his bust. The house is the color of a faded rose. The wall facing the street has two windows with shutters. The facade is done with a cornice and pilasters. The bust itself is on a low pedestal, Cioran's face re

ndered realistically and unskillfully. A folk artist might have done it, imitating refined art. The work is "small, modest, and without qualities" aside from its resemblance to the original, but it suits this village square. Every day, herds of cows and sheep pass it, leaving behind their warmth and smell. Neither the wide world nor Paris left any mark on that face. It is sad and tired. Such men sit in the pub next to the barber and in the store-shed under the grapevine. Everything looks as if someone here had made his dream come true, granted his final wish.

"Acel blestemat, acel splendid Ră inari."

Our Leader

BUT THAT'S WHAT it's like: any moment you take the wrong turn, stumble, get lost— geography's no help—and forget the objective eye. Nothing is as it first appears; splinters of meaning lurk everywhere, and your mind catches on them like pants on barbed wire. You can't simply write, for example, that we crossed the border at Siret at night on foot, and the Romanian guards, who kept in check the entire passageway and five buses carrying dozens of tons of contraband, let us through with a gruff but friendly laugh. On the other side, there was only the night. We waited for something to come from Ukraine and take us, but nothing came, no old Lada, no Dacia. It's strange finding yourself in a foreign land when the only scenery is the dark. Off to a side, crawling shadows beyond the glass, so we went in their direction, because at that hour a man is like a moth, drawn to any light. In the border tavern, two guys sat at a small table playing a game resembling dominoes. We ordered coffee. The bartender made it in a saucepan on a hot plate. It was good, strong. Hearing us speak Polish, he tried too, but we understood only babka ( "grandmother") and Wrocław. We asked about the bus or whatever, but he spread his arms and said something like "dimineaŢă tîrg in Suceava." In that blue, breath-humid light I drank Bihor palinka for the first time. It was worse than any Hungarian brandy, but it warmed, and I wanted something more than coffee since this fellow had a grandmother in Wrocław.

Dukla

Dukla On the Road to Babadag

On the Road to Babadag Nine

Nine