- Home

- Andrzej Stasiuk

Dukla Page 5

Dukla Read online

Page 5

That’s why I keep returning to this story from over twenty years ago. I’m convinced it’s composed of the same basic elements that the vortex of time arranges in different constellations, but whose nature remains unchanged, the way that water, salt, and metals form into various kinds of bodies so as to save us from boredom. Dukla was made of the same atoms, and so was that summer, when I went sniffing along her trail in the heat with a handful of sand in the pocket of my Odra jeans, and the sand diminished as the quartz rubbed through the cotton, disappearing or turning into an intangible dust.

From time to time I’d slip my hand in, take out a few grains, and taste them. I’d leave them on my tongue, press them against the roof of my mouth, and in the end my saliva would wash the particles away.

I’d swing by the beach. People were lying on the shore as if the waves had thrown them there. There was a smell of singed fat. Every so often they entered the water and thrashed about like fish on a hook. There was no intermediate state—either immobility or hysteria. But she wasn’t there.

It was as though the brown color of her flesh didn’t depend on the sun, as if she’d been born that way, or she could absorb the light of the moon by night. I roamed among the bare bodies, fully dressed like some kind of bashful pervert. The breasts, buttocks, thighs of the other women made no more of an impression on me than my little sister’s dolls. There was something ludicrous about those lifelessly toiling bodies. They lay there like stuck-out tongues, gasping for breath. I was thirteen years old and I couldn’t understand voluntary motionlessness. I would climb the steep stairs, nose around among the shacks, circle her cabin. It always looked the same. Open window, thick curtains, and a silence so profound it could have hidden anything. The pink walls took on an almost black hue in the glare of the day. They were so distinct, so separate from the world and so terrifyingly real, it was as if they were made of some substance so dense it absorbed the sunlight to the very last drop. Darkness so very evident is only ever found in dreams, or immediately after an attack of sunstroke. I’d be rescued by the tin roof of the cafeteria, a bottle of orangeade, and the fear of being unmasked. I would walk away, trail through the dust of the deserted village, and usually end up at the Ruch Club, where it was always cool and the dark smell of cinnamon cookies hung in the air. The turned-off television would be waiting for the evening, the server in her white apron sat with her elbows on the countertop, staring into her daydreams. In the gloom of the place she looked so lonely that despite myself I felt I could trust her, sensing we were linked by something rooted in boundless melancholy. I took my fruit juice and drank it at a metal table, repeating the gestures and grimaces I’d observed men making when they would disgustedly take a mouthful of bitter beer.

I performed my dour ritual every day, but in vain. I was convinced she’d left. Gone. All the same I kept returning to the old places. Sadness stupefies even more than hope.

Then, one afternoon something white moved on the porch of her cabin. True, it wasn’t actually her, but it was her white dress. It was hanging on a line strung between the pillars. There was a gentle breeze. Next to the dress hung a pair of white panties stuck up with two clothespins. A gust of wind lifted them in my direction. It was blowing diagonally from upriver, in other words from the east. I was entranced by the sight. I forgot where I was. The white cotton—rounded, filled-out, taut—recreated the shape of her body. The sweltering, unseen afternoon had slipped into her underwear so as to play havoc with my imagination. It was then I understood that she was as vast as the day is long, as all the air, all the world, that she had no end and no beginning, that she was surrounding me on all sides, that I was in her, that this white scrap of fabric was merely a sign of her all-embracing presence, a signal for a blind man, a concession to the imperfection of the senses. I felt the soft, warm touch of her bronzed skin. Because if she could be so great that she was invisible, it meant her thigh or her knee could reach all the way here, those few yards. I half closed my eyes and in the middle of that trash-strewn, godforsaken place I surrendered to the caress. My ears and cheeks burned. I rubbed against myself like a cat. Her condensed, elusive presence was so palpable it obscured reality. The gust of air that had passed through her panties formed into a living, pulsing body. I think I moved forward, took a step or two in that direction, imagining the objects around me—the brightly painted cabins, the flag over the beach, the tops of the trees, and all the rest—to be a dream or an illusion.

Suddenly the door to the porch opened and her skinny girlfriend from the beach came out. She was wearing the same bathing suit. She gave me a hostile look and snapped: “What do you want?” She took in the laundry. As she disappeared back into the cabin she gave me a last unfriendly glance over her shoulder.

At that time I made no attempt to work out the relationship between the two women. It seemed natural that beauty should be found in the company of ugliness. Her girlfriend had a pale, wan face and short mousy hair. She looked like a young boy who’d grown old before he’d reached adulthood. Her pallid, bony body moved without an ounce of grace, as if it was overcoming exhaustion or the resistance of its own sinews by sheer effort of will. I’d seen her at the cafeteria buying something to drink, or with her basket at the store in the village. She walked quickly. She wore shabby clogs that twisted painfully on the cobblestones. She kept her head down as she passed people. She never spoke with anyone. One time, in the store a half-drunk guy started talking to her. She left immediately. I think it was her who had washed the other one’s clothes.

Time died away between Saturdays. It lost its light, transparent quality. It swelled, thickened, became inert, stuck to the body, and my life came to resemble a march into the wind. I felt like I was trying to run in water up to my chest. My gestures trailed behind me long after I’d made them. I was convinced they left traces in the air. Because back then time was very much like air. Or water. On Saturday evenings, though, it regained its rightful form. It flowed so quickly that it got ahead of me. I could see it fleeing, the way landscapes slip away from the window of a train. Nothing could be done. In theory they remain where they are, but you have the feeling that it’s the landscapes leaving us behind, not the other way around.

She came to every dance. For a month. Always alone. Her companion must have stayed in the cabin, though there was no light to be seen in the window. She sat in the dark, glowing phosphorically like an old skeleton. That must have been enough for her. In the meantime, her friend was gyrating amid the other dancers, animated, impetuous, and taut in her magnificent integument, as if she were about to burst, explode, from an excess of her own existence. The eyes of the farm boys followed her as though attached by strings, but none of them was brave enough. She guessed their thoughts, and once in a while she would assail one or another of them. She’d lean back slightly, push out her chest, and they’d be left dumbstruck, treading on their own shoelaces, enclosed in a whirl of air she had set in motion, while she was already elsewhere, engrossed in herself, guiltless and absent.

Older folks came to the dances too. Women in particular. They brought with them the barn-dance custom of sitting on benches around the walls and, as they swallowed the dust, sharpening their tongues or simply watching without a word, sinking into their own past life like a vivid dream with eyes wide open. Here there was no dust and no walls, but there were a few benches around the dance floor. There they sat, fifty or sixty years old, in green and brown and black head scarves that in the darkness resembled hoods. As they talked, their gold teeth flashed like lit matches. They looked like jurors in a courtroom. In twos and threes, their heads leaning in to one another, they examined the throng and muttered among themselves, not letting the spinning couples out of their sight for a second.

As usual I dodged about, following her white dress. I orbited the hubbub of the dance, lurking at its edges, intent and at the same time hopelessly vulnerable, my secret inscribed on my face. She would be turn

ing tight circles in the middle of the dance floor, widening them then once again shrinking to the irreducible shape of her own outline; but even when she was virtually standing in place, restricted, hemmed in by the crowd, she kept dancing, she danced without moving, but she was just as impetuous, because her presence alone was a scandal and a provocation. Perhaps the blood surged so intensely through her body that its pulse was visible. All at once, in one of those moments of stillness as the singer Irena Jarocka was taking a breath, in the split second of half-quiet I heard the voice of an old woman from a nearby bench. She said, “Whore,” then the music started up again, drawing the hundreds of dancers into its circulation.

The girl couldn’t have heard it. No one did aside from me. Everything was taking its regular course. Some people were moving off toward the bushes.

They would come back unsteadier on their feet, or with their clothes in greater disarray, or they wouldn’t come back at all, and it would only be the morning dew that woke them in a haystack, which in those parts was known as a mendel, the old measure of fifteen, because each stack was made of fifteen sheaves of hay. So everything was the way it always was. “Yellow Autumn Leaf,” a slow number, offered a chance to catch your breath and whisper blandishments. “She gave me it without a word / And yet I knew full well.” Some of the guys wore flares decorated with gold studs and close-fitting shirts patterned with vertical zigzags in all the colors of the rainbow. The coolest girls were in tight cotton pants that were cream-colored with a fine brown check. What else? I guess big colorful East German Ruhl watches on wrists, and huge bright plastic signet rings in the shape of cut stones: purple, yellow, green, or white. Around their necks they had rectangular wooden pendants that bore an enameled photo of ABBA, strung on a thin cord. Slade too, I think. There were masses of such things at church fair stalls in August and you could take your pick, so there must have been other heroes too. Yes, there was Hoss, Ben, the other Cartwrights from Bonanza. So nothing special was going on. The world abided in its established fluctuating form and beer couldn’t have cost more than four zlotys, while Start cigarettes in the rough orange-colored soft packs were 5.50, but something like a fissure in existence had opened up in front of me, something like an alluring wound in the skin of the everyday. I didn’t yet know how to translate that word into the language of reality. But I did know its taste: acrid, dark, intense, and bitter, like things that despite ourselves we’re unable to resist, and in fact do not wish to. The word, spoken in a harsh lifeless voice, unfolded in the air and wrapped her figure in an aura. Now she was dancing in the glow of her own body and the glow of the imprecation.

I was thirteen years old and there was much I didn’t understand. All I sensed was that in a single moment my love had ceased to be an innocent and embarrassing game, and had become something forbidden. I was thirteen years old and I could feel that beauty always involved peril, that in essence it was a form of evil, a form that we may desire as if we were desiring good.

Now, passing through Żmigród, I can see this very clearly. The bus picks up one tipsy passenger, stops at the little town square then heads downhill, turning left by Leśko’s dairy and moving along the strange road that neatly separates the hills on the left from the level terrain on the right. But back then everything was simply a play of shadows, smells, sounds. A bizarre arrangement of the physical manifestations of the world, which formed themselves into a momentary passageway, a channel that led to the other side of time and landscape. This flip side of the visible was essentially identical to its regular face, except it was infinitely more attractive because it was unaffected by gravity and completely given over to the laws of the imagination. This one word coming into contact with her body had turned inside out, become its own opposite, so as once and for all to shake my faith in unambiguity.

One time I went to Dukla in the winter. It was January, though it was more like a snowy November or a permanent dusk. Sky and earth were merged. The sprawling outskirts of Jasło, the hangarlike warehouses, jagged rows of snow fences, indeterminate outlines of people twenty yards from the roadway, houses with motionless smoke issuing from their chimneys, and all the other familiar things—everything only half existed. A memory of archetypes was needed to uncover its true meaning and purpose. “This is a house. This is a dog. This is Jane’s cat.” The mist-flattened contours barely revealed themselves. Everything except what was definitively black belonged to this half-snowy, half-watery state of convergence. It was a color-blind dream, or an old dying television set. Even the black—the vertical strokes of trees, the horizontal lines of balustrades on the footbridges—even these things looked more like their own shadows. It was as if the objects themselves had vanished, leaving only their faint impressions in a suspension of gray light. On top of everything it so happened that I’d not slept the previous night and had greeted the day on my feet. I’d not crossed the boundary of waking. Unreality had taken hold of that Tuesday and wouldn’t let go. Right at the beginning, in Gorlice, at seven in the morning, when I’d been buying a Red Bull for the road, the guy in front of me in line was wearing classic wide 1970s pants with a pressed seam and a so-called “cool jacket,” nylon, all black but with cornflower-blue sleeves, in other words early Gierek, Różyckiego bazaar in Warsaw, with a broad plastic zipper. He stood there shivering, though it was warm in the store. Then, when his turn came he said: “One from the fridge, please, one of those with the penguin.” He left the store, shuffling with the familiar step of someone whose foot doesn’t entirely believe that when it rises from the ground, the ground is going to wait for it to return.

Before I got on the bus I’d met Mr. Marek, who as usual told me the story about how he’d once been rich and had bought dinner for someone or other. As usual I gave Mr. Marek something toward his ticket, and as usual he headed straight for the store.

But now I was passing through Jasło already. Under the bridge the Wisłok looked like a blacktop highway. Nothing was reflected in it. The bus was long and comfortable. It rocked and hummed, and up front a TV monitor hanging from the roof was showing a furiously colorful movie, probably from California, because there were palm trees, swimming pools, stretch limos, naked women, and blood was flowing. The screen looked like a window onto the truer side of the world. Around me, all the way to the horizon everything was dull and indistinct, while up there was a bright rectangle of heavenly colors and people devoting themselves to wealth, love, and death. The fellow sitting next to me took off his cap with earflaps and stared, now at the screen, now out the window. Both views must have bored him, because in the end he crossed his arms on his belly and fell asleep.

In Krosno, water was dripping from the rooftops. The ingeniously wrought roofs of Krosno are designed for thaws and rain. The water eddies, gurgles, meanders, and drips in those miraculous products of the roofer’s art as if they were some kind of meteorological carillon, till in the end they find their gutter and trickle down to the street; there, old folks walk timidly along, their elbows raised like the wings of startled chickens, because warmth has reached the rooftops but down below, on the sidewalk, it’s still freezing, and glassy tongues protrude from the jaws of the drainpipes. That was how it was. I was catching my balance, I had a good hour till my connecting bus to Barwinek. Mist, water, and the alienation of sleeplessness, when even in a clean shirt and with money in his pocket a guy feels like an old wino.

I tried saving myself by having a beer with a large shot of cassis in it, but it was just as indistinct as everything else. Haziness was seeping into everything both alive and dead. I thought to myself that before I got there Dukla would disappear, evaporate into the air like an old memory. I wanted to buy Mr. Michalak’s guide, Dukla and Surroundings. I’d seen it in a shop window one time in Dukla, but it had been a Sunday and the store was closed. Now I went looking for it in Krosno. I entered the bookstore on the street that swings to the right beyond the bridge and wraps around the base of the old town. Inside

it was quiet and warm. A priest was conferring in an undertone with the young woman behind the counter. Radio Maryja was playing in one corner. There was a smell of turpentine and printed matter. The books were arranged on shelves around the walls. Most of them were about holiness and miracles, but there were also items about the Masons, the Mormons, Manson, and the worldwide conspiracy. There wasn’t anything about Dukla. I tried to eavesdrop on the conversation between the priest and the clerk, but they were whispering softly, conspiratorially, their heads together.

I couldn’t see the priest’s face. Radio Maryja was playing its favorite song, with a catchy harmonica melody and a mixed choir singing about how victory would come to the white eagle and the Polish race. Dressed in black and leaning forward, the priest looked a little like a conspirator. He left the store at a smart pace, I saw him toss a bundle of books into an old Opel and drive off. The young woman’s perfume wafted around the place. The air had been disturbed by the cleric and had drawn the scent toward the door. The clerk wore glasses. Or at least she should have.

After that there was the immensity of the Krosno bus station. The tarmac was vast as an airport, tiny beat-up old buses with signs saying Krempna, Wisłoczek, Zyndranowa were waiting where there should have been jet liners taking off. My bus was right near the end; it was yellow and so very helpless you had the urge to take it in your fingers, lead it out onto the roadway, give it a gentle push, and say: Come on little one, don’t be afraid, off you go.

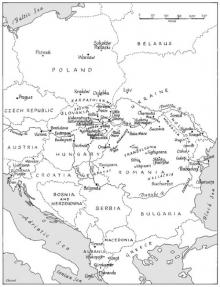

I wasn’t mistaken. Dukla was in danger of ceasing to exist. As usual I took the alley between Mr. Szczurek’s photography studio and the display cabinet of Mr. Kogut, doctor of veterinary science. The town hall could barely be seen against the sky. It looked like a piece of the latter that had been cut out with scissors and had slipped down a little ways and come to rest on the pavement. A two-dimensional stage decoration with little cardboard doors at the top. The air pressure was plummeting, but the air itself remained still. The warm southern halny wind hadn’t yet begun to blow. Right now it was probably gathering strength over the Great Hungarian Plain, stretching out its paw and feeling the south side of the Carpathians for fissures, low-lying passes, and broader saddles by which it could break through and descend on the unsuspecting Podgórze region, sowing mental havoc in its inhabitants. Just in case, then, I stepped into the bar at the tourist office.

Dukla

Dukla On the Road to Babadag

On the Road to Babadag Nine

Nine