- Home

- Andrzej Stasiuk

Dukla Page 7

Dukla Read online

Page 7

So there I stood, almost motionless, performing my blasphemous parody of her being. The faucets were made of black ebonite and had no distinguishing features. A broken match lay on the plastic soap shelf. Its brown head had faded and stained the wooden stem pink. I stood almost stock-still. I was afraid I’d disturb the air, and the air would disturb the rest. Because it was all like a living grave, like something put to sleep forever.

At that moment the bell in the little wooden church started ringing. It was the six o’clock Mass, said for a few old women in dark head scarves for whom only two candles were lit on the altar, the sacristan doing the job of the altar boys. I stepped out very slowly, backward, closing the curtain behind me. I retreated till I felt the wall.

Outside, a woman in a drab-colored apron stood with a mop and bucket, talking to a fat man. I passed between them, interrupting their conversation. When I was a few yards further on I heard the cleaning lady’s raised voice: “What did I tell you, boss? The little buggers come in here to take a piss, they do . . .”

The man made some reply, but the woman wasn’t convinced and kept repeating what she’d said, though I couldn’t hear the words anymore. I walked slowly. Under the metal overhang outside the café there were only locals. The next day I was leaving. Today I was supposed to pack.

That other day, before D. and I headed for Komańcza, we took a turn around the market square in Dukla. There wasn’t a living soul. Everyone had either joined the funeral procession or they were at home waiting for the others to come back, so there’d be someone to talk to. D. peered through a dark window into a bicycle repair shop. He called me over. “There’s some kind of trumpet in there,” he said. “With the bicycles?” I asked, and looked in. It was true—on the wall of the workshop, among the frames, pedals and everything else there was something golden, though you couldn’t tell if it was a trombone or a French horn. In any case it shone there, golden and mysterious, and somehow sad and lonely, since all the other brass instruments were at the funeral. It was as if it had stayed behind as a punishment, or because of old age.

After that I wanted to show D. the big veranda and the mansion and we crossed in front of the buildings to find the little passage that led down a few steps to the Dukielka. As we were passing a low wall on the corner of the square, a figure sprang out at us like a jack-in-the-box from behind the wall, landed plumb on its two feet right in front of us, and asked for a cigarette. We didn’t even have time to notice if it was a guy or a girl, it was all hairy and curly and indistinct from alcohol. Whoever it was took four smokes “for my girlfriend” and disappeared just as energetically back behind the wall. It was only the shaking of the bushes on the other side that made us believe the incident had been real.

Then later I was drawn to those steps, which seemed to lead underground. It was what was left of a public lavatory. The old wooden door hung off its hinges. I went inside. There was nothing there, just semidarkness and ruins. Nothing whole, just bits and pieces. Places where faucets had been, rusty marks left from fittings, porcelain shards of toilets, and everywhere flakes of paint from the walls. Dust, cobwebs, scraps of newspaper, broken glass, disintegrating red oddments of iron, rubble, and dried shit. And gray light from a small street-level window. Outside the day was sunny, but in here the brightness failed. There are places like that, but they usually appear in dreams. I suddenly felt a twinge of fright. Or rather horror, the cold touch of the oldest fear. It must have been more or less what people felt when they became aware of the existence of time, when they realized they were immobile, that they were being left behind and nothing could ever be done about it.

I stood without moving; my skin crept. In this abandoned, decay-filled john I’d seen matter in its ultimate state of collapse and abandonment. The minutes and years had simply entered into things and broken them from within. The same thing that always happens everywhere. I’d had to live for thirty-six years to have come this far.

With heart in mouth, my spine tingling, I headed up again. I climbed slowly, one step after another, back to the street. The bells of Mary Magdalene were ringing. It was then that I decided to describe it all.

II.

I always wanted to write a book about light. I never could find anything else more reminiscent of eternity. I never was able to imagine things that don’t exist. That always seemed a waste of time to me, just like the stubborn search for the Unknown, which only ever ends up looking like an assemblage of old, familiar things in slightly souped-up form. Events and objects either come to an end, or perish, or collapse under their own weight, and if I observe them and describe them it’s only because they refract the brightness, shape it, and give it a form that we’re capable of comprehending.

The train station at Jasło was well lit and deserted. The sun was shining for the first time in a week. The trains looked benign. It’s almost always like that at provincial stations: the cars remind you of the toy train set from your childhood, and the locomotives display their vivid original colors in the glare—green, black, the red of the wheel spokes and the plaque bearing eagle and engine number.

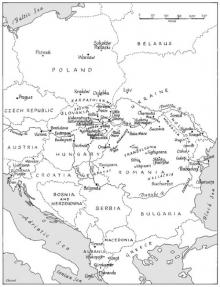

When it’s hot, the brown ties give off a nostalgic smell that makes you long to take a journey without a destination, moving slowly and tediously across a still, ornamental landscape. You can get out, cross the tracks where it’s not permitted, in full view of the conductor in his raspberry-red cap, and nothing happens. The cars have white signboards on their sides with place-names: Zagórz, Zagórzany, Krynica, or Khyriv over the Ukrainian border, where fat women are waiting to take the same train when it comes back; they’ll be lugging stacks of knockoff Cubans, spirits, and packs of pirate Pall Malls, so as to sell it all in Krościenko and head back home the same day.

The air has a golden tinge. The poplars and birches are in blossom. Dust hovers over the station like a mild narcotic. The ticket costs two zlotys something, while the journey is eighteen miles or so and will take the best part of an hour.

The compartment was empty, as was the whole train, it seemed. It smelled of stale cigarette smoke, while exhaust fumes from the diesel locomotive drifted in through the window. To the north, on the far side of the valley of the Jasiółka, lay the ridges of the Strzyżów heights. The leafless beech woods shone in the sun like ruddy fur. I was going to Dukla yet again. There were people working in the fields. The plowed earth looked like chocolate. They were sowing, harrowing, planting, lone women leaning on their hoes and following the train with their eyes. Some of them were simply sitting facing the sun, half-leaning in repose, their legs spread, propped on an elbow, stretched out like heterothermic animals in the too-early heat. Insectlike vehicles constructed from old WSK motorbikes—three wheels, engine whining at its highest possible rpm, and a flat trailer drawn behind at walking pace—were ascending the hillside. Loaded with grain or bricks of saltpeter, they crawled over the muddy ground beneath the blue sky like docile beasts of a newly domesticated species. There were a mechanical specialty of the poorer regions. Some had a regular little cart instead of a trailer. They were a transitional hybrid, halfway between horse-drawn plow and tractor. They paused at the highest point, the men strapped on a canvas apron, then they walked downhill sowing by hand like in the old days, in a dancelike rhythm: step, broad fling, step, take a handful, step, broad fling. I was in the train smoking, yet despite the distance I could hear the noise of their rubber boots as they trod heavily, a resonant sound that was a little like a slap, a little like flesh.

So it was. Barely half a mile a minute, so everything lasted long enough in the air that it could take hold in the memory, leaving an impression like the millions of other images that you then carry inside yourself, and that’s why people are like crazy stereoscopes, and life is like a hallucination, because nothing that you see is what it is. Something’s always showing through from underneath, rising to the surface like a drop of olive oil, opalescent, glistening, luring you like a fiendish

trick, a will-o’-the-wisp, a temptation without end. It’s impossible to touch anything without disturbing something else. Like in an old house where a single quiet step sets glass rattling in a cabinet two rooms away. That’s how the mind works, how it protects you from madness, because life would be impossible if events were lodged in time like a nail hammered into the wall. The spiderweb of memory enwraps the head, thanks to which the present is equally hazy, and you can be confident it’ll turn almost entirely painlessly into the past.

In Tarnowiec white clouds hung over the station. From the horizontal gaps between them a golden mist descended onto a wall bearing the inscription “Sendecja are Jewz.” The old-fashioned railway signals were lowered. I wanted to select an event from my life, but for the moment none seemed better than any other.

Then four men got into the compartment next to mine. I’d seen them walking along the deserted platform. They looked like workers who’d managed to get off before the factory whistle blew. They were like children playing hooky. Through the thin partition I could hear them moving about, vigorously and casually making themselves comfortable, perhaps putting their feet up on the seats, and I immediately smelled cheap Klubowe cigarettes. Before the train even pulled out they were deep in a lively conversation. They were talking about televisions, the way boys talk about cars, about mythical makes, imaginary specifications, miraculous capabilities. Sony, Samsung, Curtis, Panasonic, Phillips . . . But it didn’t sound like the usual unthinking latter-day incantations. The guys were speaking about the different kinds of light emitted from various sorts of screens. This one was too cold, that one too purple, a third one too brilliant and unreal, painful to the human eye; another kind was too soft, sugary-sweet, an insult to the natural dignity of the colors of light. They were seeking an ideal, combining the qualities of different electronic mechanisms the way you mix paints, or spend hours setting up the lights on a film set so as for one brief moment to capture reality in a single unique and unrepeatable second, when for the blink of an eye it coincides with the imagination. They were trying to reach a compromise between the visible and the represented. There wasn’t a word about things technical, not an ounce of doltish idolatry. At least till Jedlicze, where they got out amid the silvery purification columns wrapped in labyrinths of refinery piping. Maybe the conversation continued? Maybe they were on their way to work in that technoscape, at the edge of which, without a care in the world, cows were grazing, horses working, and age-old poverty was slowly turning into a rustic paysage.

And so it was all the way to Krosno.

In the distance, with titillating inscriptions on their red and yellow tarpaulins, huge trucks move along: the glistening projectiles of Volvo tankers, green Mercedes vans, DAF articulated truck-trailers, polished Jelczes, snow-white Scanias, and among them the small fry of regular automobiles like lesser stones in the necklace of capitalism: amethysts, emeralds, rubies, opals, sapphires—all in sunlight, glinting, from east to west and back again, all the way across Europe with a sticky squeal of rubber on heated asphalt, with fat guys at the wheel in leather jackets, a Marlboro between their lips and the Blaupunkt cranked up to the max, pedal to the metal like they were being chased by the devil, or they were chasing him (who knows), as though amid the ancient unmoving hills time had hollowed out a narrow passageway in which it could accelerate as if it intended to make up for entire centuries, leave everything behind and get to somewhere outside of material, inhabited space. That was how it looked.

On the hillsides, on flat patches along the road, at the edges of alder thickets, the locals stood and watched as their world broke off like a piece of land or an ice floe and drifted backward, though it looked as if it was staying in place. The iron harrows on the wagons, the pitchforks, harnesses, rubber boots on bare feet, the symbiotic smells of stable and home, the powerful age-old interweaving of human and animal existence, curdled milk, potatoes, eggs, lard, no long journeys in search of trophies, no miracles or legends other than satiety and a peaceful death. They stood there, leaning on the wooden helves of their implements, rooted in the earth that would soon shake them off the way a dog shakes off water. The trembling brightly colored line of the highway ran along the bottom of the valley. In essence it was a tectonic crack, a geological fault between epochs. They were standing there watching. At least, they ought to have been. In reality they were just getting on with their work without a trace of interest, without fear, entirely engrossed in the materiality of the world, its weight, which enabled them to feel their own existence as something real.

That was how it was as I rode the train to Dukla in April, the light continually summoning things into being then annihilating them again with a cold, supernatural indifference. The outskirts of Krosno were flat and industrial. Warehouses, sheds, lockups, general devastation. There was something lying by the tracks. Maybe someone had been supposed to load it up and take it away, but now it didn’t look like it would be worth the effort. Branch lines ran off amid low buildings. They were coated in rust. Scrub, nooks and corners, the smell of hot tar roofs—just the place to sit yourself down, drink cheap fruit wine, and watch the long-distance trains that no one ever gets on. Sun-drenched walls, benches made of a handful of bricks and a plank, the glitter of green and brown broken glass, white bottle caps, colorful tongues of trash slithering down the embankments, and a girl of twelve in her mother’s high heels pushing an enameled stroller that was fifteen years old. Railroad suburbs always look like a no-man’s-land—no one either lives or works here, so everything’s permissible, while the lazy trains, either gathering speed or slowing down, give off an unreal aura, and everything is plunged in the half-sleep of the borderland between childhood and adulthood, where dreams and reality cannot be told apart.

The Magnum Disco Night Club Roundhouse was empty inside. The openwork glass rotunda had shared the fate of the rest of the neighborhood. The only thing left from when the place had been open was the sign. Though in fact you couldn’t tell if there’d ever been any action here. Maybe it was still to come? It looked as much like a renovation as a demolition. A glass-built soap bubble growing out of a patch of ground strewn with scrap iron and concrete—the slightest prick and there’d be nothing left but empty space. I tried to imagine a night out under that pathetic dome, in the morbid quiver of strobe lighting, with a rumble of trains behind your back. The image I got was of a terrarium, or a dance of skeletons.

The conductor came by, but he didn’t ask for my ticket. He just said, “We’ll be there soon.” As if I looked like a newcomer, like someone who needed help.

I had an hour till the bus for Dukla. Too long to wait, too short for a decent walk, just enough time for a veal cutlet in the Smerf Café, where up till then I’d never seen another soul, though it was very reasonably priced, clean, you could get a meal no less tasty than the national average for around thirty thousand zlotys. The time was also just right for a beer at the store with the one outside table, the place to the right beyond the post office, along with a guy who’d wheeled his bike into the beer garden and leaned it against the table, though it was an old Ural with a leather saddle like on a Cossack horse, and a spring shaped like an electric heating coil.

Then later, on the bus, I thought about how Dukla deserved a rail connection. If not a proper one, than at least a narrow-gauge line. Once or twice a day a little locomotive would roll up to a low gravel-covered platform somewhere between Węgierski Trakt and the bus station. The tracks would divide the old part of town from the flashy nouveau-riche neighborhood copied from TV shows and things remembered from seasonal labor in the Reich. Not tracks even, just one track and a passing place, say, in Miejsce Piastowe. The hard, insistent clatter, wooden seats in narrow cars with windows that instead of handles have leather grips like on a suitcase. Smoking’s allowed on the entire train, it makes no difference at all, because the south wind from over the pass blows coal smoke in through every crack and crevice. From Krosno it tak

es a good two hours, bouncing up and down, with the rattle of couplings and the sideways swaying, so every once in a while you have to go out on the observation platform to rest your bones, and there in unmown ditches skinny cows are being grazed by children, because it’s high summer, school vacation, and a landscape without a cowherd is a fearful wrong.

Dukla

Dukla On the Road to Babadag

On the Road to Babadag Nine

Nine